Damage model

Table of contents

Direct damage

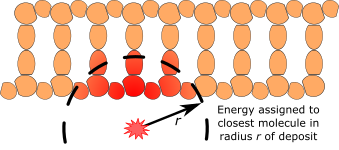

Direct Damage occurs when energy from physical processes is deposited near a DNA molecule. In molecularDNA, we associate damage either with a ‘strand’ molecule (sugar or phosphate placement) or a base molecule.

The maximum distance from the centre of a molecule which can result in any energy deposition tied to that model is called the direct interaction range and can be set using dnageom/interactionDirectRange.

To assign damage, the program looks up all molecules with the direct interaction range of a given energy deposition and assigns the damage to the closest molecule.

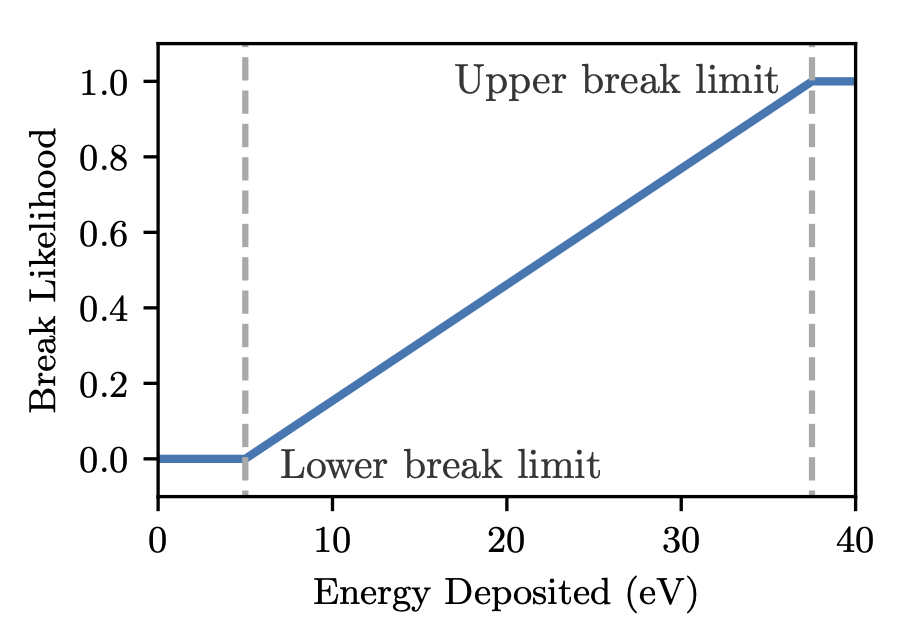

In the literature direct strand break damage models typically take the sum of the energy depositions in the sugar-phosphate part of the DNA strand and calculate the chance of a break based on the energy deposition. We simulate this using the /dnadamage/directDamageLower and /dnadamage/directDamageUpper commands. Essentially:

- Energy deposition below directDamageLower never causes a break

- Energy deposition above directDamageUpper always causes a break

- Between these bounds, the likelihood of a break rises uniformly

The likelihood of a break, for a lower bound of 5 eV and an upper bound of 37.5 eV is shown below

Some models assume a step likelihood function for physical damage. This can be modelled by setting /dnadamage/directDamageLower and /dnadamage/directDamageUpper to the same value.

Indirect damage

Indirect damage is scored when a chemical reaction leads to a strand break. The chemical reactions between radicals and DNA elements themselves are defined in the chemistry model through the ChemistryList class.

The phosphate part of the sugar-phosphate backbone rarely takes part in reactions (reactions between radicals and phosphate are not even defined in the simulation), so the main factors in the indirect damage model are the likelihoods that a reaction between a radical and the DNA backbone lead to a single strand break (SSB).

Each probability is defined through the macro interface as below :

| Reaction | Macro Command |

|---|---|

| \(Pr(\ce{e^{-}_{aq}} + \mathrm{Sugar} \rightarrow \mathrm{SSB})\) | /dnadamage/indirectEaqStrandChance |

| \(Pr(H^{\bullet} + \mathrm{Sugar} \rightarrow \mathrm{SSB})\) | /dnadamage/indirectHStrandChance |

| \(Pr(\ce{^{\bullet}OH} + \mathrm{Sugar} \rightarrow \mathrm{SSB})\) | /dnadamage/indirectOHStrandChance |

Base damage is modelled through a similar interface, though two steps are provided for the modelling of both base damage generally, and also strand break induction (while this might seem redundant, it was coded for a level of flexibility).

For a given base, we can consider separately the likelihood that the chemical reaction between the base and the radical causes damage to the base pair, and the likelihood it causes a strand break. In the case of \(\ce{^{\bullet}OH}\) /dnadamage/indirectOHBaseChance 0.5 would set the likelihood that the simulation should consider a reaction between \(\ce{^{\bullet}OH}\) and a base as damage as 50%. If base damage does occur, /dnadamage/inductionOHChance 0.4 would mean that following base damage, the chance of that damage causing an SSB is 40%. Note that these are dependent events, so the likelihood of the reaction causing an SSB is 20%.

For most work, you would probably consider all chemical reactions with a base as base damage, but assume these don’t lead to SSBs. This requires the following settings for all radicals:

/dnadamage/indirectOHBaseChance 1.0

/dnadamage/inductionOHChance 0.0

Damage classification model

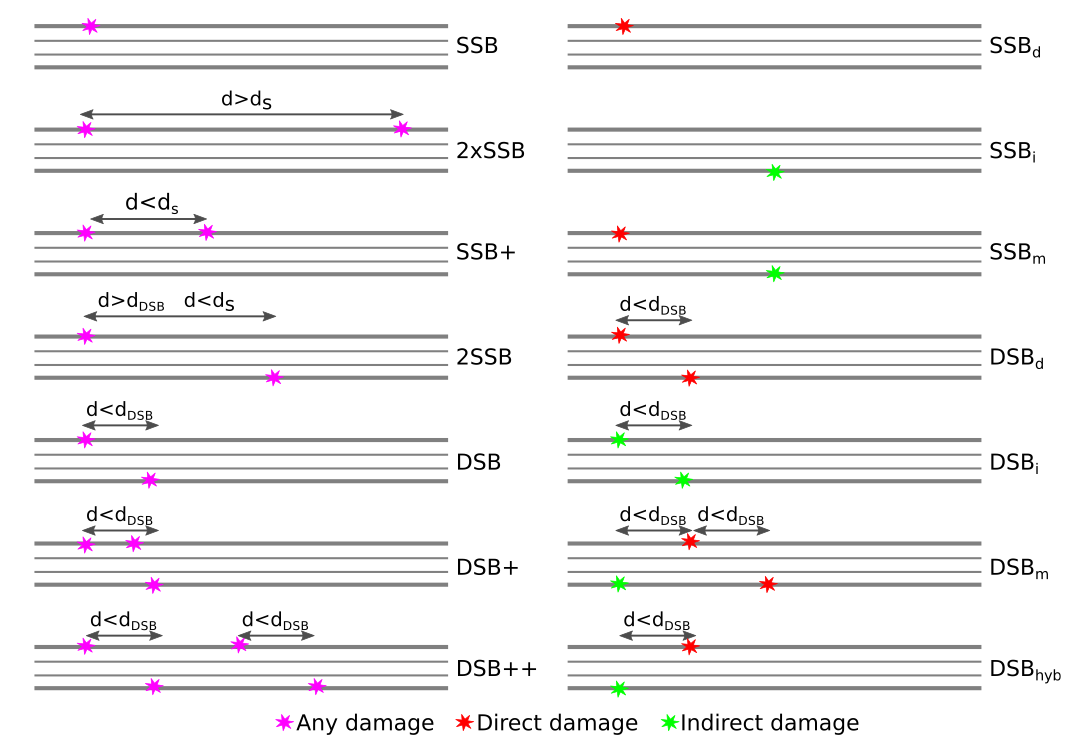

Breaks in a DNA segment are classified both by complexity (left) and source (right) [1] . The model entails two parameters, dDSB is the maximum separation between two damage sites on alternate sides of a DNA strand for us to consider that a DSB has occurred (typically dDSB = 10 bp). ds is the distance between two damage sites for us to consider that the damage events should be considered as two separate breakages (yielding two separate segments that need classification). Whilst many of the classifications are clear, we note that a DSB+ requires a DSB and at least one additional break within a ten base pair separation, while a DSB++ requires at least two DSBs along the segment, regardless of whether they are within dDSB of each other or not. For break complexity, the most complex break type is always chosen. When classifying breaks by source, we pay attention not to all damage along the strand, but to the damage which causes DSBs only. DSBs from only indirect sources are classified as DSBi, and those only from direct sources are classified as DSBd. DSBhyb is distinguished from DSBm, as DSBhyb requires that the DSB not occur in the absence of indirect damage. Otherwise, a break caused by indirect and direct sources is classified as DSBm. Where a segment contains both indirect and direct DSBs, it is classified as DSBm. Similarly, when a segment contains a DSB classified as DSBhyb in conjunction with a direct DSB or mixed DSB, it takes the DSBm classification, otherwise it keeps the classification DSBhyb.

Radical scavenging

One of the most important parameters in the simulation is /dnageom/radicalKillDistance which specifies the spatial region in which we calculate chemistry. This parameter is complimentary with what other simulations would model as scavenging or an early simulation cut-off time, in that it is linked to the distance a radical is expected to diffuse before the simulation ends.

In particular, for a radical with a diffusion constant \(D_c\), we expect it to diffuse a distance \(\bar{x}\) in time \(t\) as follows:

\[\bar{x} = \sqrt{6D_ct}\]For the \(\ce{^{\bullet}OH}\) radical (\(D_c=2.8\times 10^{-9}m^2s^{-1}\)), this gives \(\bar{x} = 4.09 \sqrt{t} \ \mathrm{nm}\). Typically for simulations of cells in molecularDNA, this means that a radical kill distance of 4nm-6nm yields reliable results, while larger radical kill distances would require scavenging to be more broadly implemented.

References

[1] Computational modelling of lowenergy electron-induced DNA damage by early physical and chemical events, H. Nikjoo et al., Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 71 (1997) 467–483 - link